That annoying numbering of the Psalms (Part 1)

Why the Greek is different from your English Bible

The Septuagint (a.k.a., LXX) numbering of the Psalms causes considerable confusion for many folks. Why is it different that the numbering in the Hebrew Bible and nearly all English translations of the Bible? The psalm numbers start off the same, but then at Psalm 9 the Septuagint starts to lag by 1, and stays behind by 1 until the hundred-teens where is gets further behind. But it catches up so that by the end, the last several psalms have the same number. [For the purposes of this post, I am excluding Septuagint Psalm 151.]

The short answer is that the Greek Septuagint psalms have the correct (or at least oldest) numbering and most English psalters are wrong.

“Wrong?” Yes, wrong. “How can you say that?” I can say that because psalms are self-contained poems, individual literary units. If I clubbed together a poem by Emily Dickenson with the lyrics of a Beatles song and told you, “This is one composition.”, I would be wrong, at least insofar as what was originally set down on paper.

Let’s start with the first point of divergence: Psalms 9-10 (Hebrew). In the Septuagint, these two psalms are a single psalm - Psalm 9. This psalm is an acrostic. That is, each verse starts with the next letter in the Hebrew alphabet. There are 8 acrostic psalms in your English Bible. Unfortunately, when translated into English (or any other language), this Hebrew art is not visible. Only the most really awkward, Scrabble-like translation could attempt to preserve it. Psalm 9 is an imperfect acrostic, like a couple others in the Bible. A few letters get skipped or flipped, but when combined, Psalm 9 begins with A,B,C (in Hebrew aleph, bet, gimel) and Psalm 10 ends with X,Y,Z (in Hebrew resh, shin, tav). That is how we know Psalm 9 and Psalm 10 were originally a single psalm.

But don’t take my word for it. Let me quote the renowned Hebrew Bible scholar, Robert Alter: “The Septuagint presents Psalms 9 and 10 as a single psalm, and there is formal evidence for the fact that it was originally one poem.” He goes on to state, “When the chapter divisions were introduced in the late Middle Ages, the editors, struggling with this imperfect text, no longer realized that it was an acrostic and broke it into two separate psalms.” (The Hebrew Bible, A Translation with Commentary, Robert Alter, 2019). From this quote, one might get the notion that those silly Protestant Christians in Europe made this dumb mistake. But Alter seems not to be wholly transparent here. In fact, the mistake exists in both of the oldest nearly complete Hebrew manuscripts in existence, the Leningrad Codex and the Aleppo Codex. The former actually numbers the psalms, using the Hebrew alphabetic numbering system; the latter has a blank line between the psalms. Here from the Leningrad Codex you can see the Hebrew numeral yod (=10) cutting the psalm in half:

And here in the Aleppo Codex you can see the clear psalm break between Psalm 9 and 10 [I also highlighted the folio number in case you wanted to navigate to it yourself online.]:

Not sure why Alter ascribes this error to the “late middle ages”. It goes back centuries earlier to the oldest known Hebrew sources at the time verses and chapters were determined.

So if you are sitting down to read Psalm 9 in its entirety in your King James Version or nearly any other English translation, you should include Psalm 10 with it, or renumber your Psalm 10 as “9b”!

This error in the numbering of the Hebrew psalms accounts for about 70% of the difference between the Septuagint and the Hebrew Bible psalm numbering.

The second numbering difference is found in Septuagint psalm 113. Up to this point we are off by 1. But here, the Septuagint again has 1 psalm that exists as 2 in the Hebrew… well this gets even more interesting. You see, both of the manuscripts mentioned above treat these 2 psalms in your English Bible as 1 psalm, just like the Septuagint. In the Leningrad Codex, where the psalms are clearly numbered, there is no number introducing Psalm 115. The next number in the codex is for what you have as Psalm 116 in your Bible. In the Leningrad Codes, just like in the Greek Septuagint, 114 and 115 are a single psalm. In the Aleppo Codex, not only is there not a blank line separating one psalm from the next, but in addition, the first line of your Psalm 115 is shown as the last cola of the last verse of your Psalm 114 (i.e., on the same line). So clearly the scribe of this codex saw these as 1 composition, just like his ancestors who translated it into Greek more than a thousand years earlier.

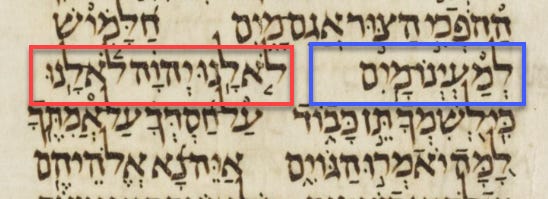

Here’s the place in the Aleppo Codex where English Psalm 114 ends and 115 begins. Keep in mind that Hebrew is read from right to left. The blue box is the end of Psalm 114 (“into springs of water”). The red box is the beginning of Psalm 115 (“not to us Lord, not to us”). All of which is contained in Septuagint Psalm 113.

Another bit of evidence that 114+115 is a single composition is the absence of an introductory superscription (e.g., “A psalm of David”). Several other psalms lack superscriptions, so by itself this is not a smoking gun. But it is a noteworthy data point.

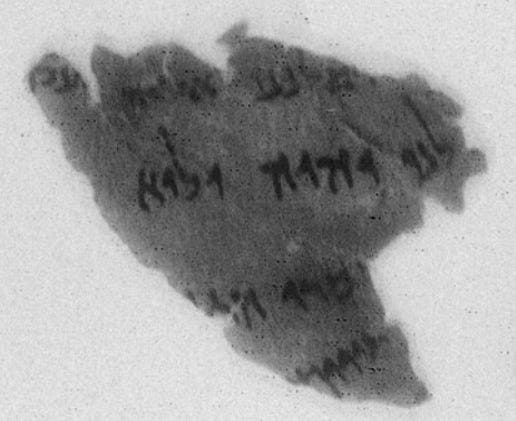

A more interesting data point comes from the Dead Sea Scrolls, 4Q96 - 4Q Ps(o) plate 1151, Fragment 10 . This little fragment below measures roughly 3x3 cm and amazingly it contains part of verse 7 of Psalm 114 and verse 1 of Psalm 115 (English numbering). A transcription of the fragment was published in 2010 by Lexham Press (4Q96 Psalms O, Logos digital Edition). The transcription includes the ending of psalm 114 and the beginning of Psalm 115 on the same line. There is no new line or vacat (space left blank) in the manuscript. How is it possible to know this from such a small fragment? It’s because of the vertical positioning of the words that exist on the fragment. We know from other manuscripts and our modern Bibles which words are missing. We know from more complete manuscripts how wide a column was for writing. This determines, on average, how many letters will be placed on a line. Using these pieces of information, a skilled transcriber can guess with some accuracy what are the missing words on each of the lines represented in the fragment. The published transcription shows the same phenomenon that we see in the Aleppo Codex: The first line of Psalm 115 is on the same line as Psalm 114.

But what about the contents of Psalms 114 and 115? Does the poetry itself indicate one way or the other if they were 1 or 2 psalms? Not really. It could go either way in my opinion. Psalm 115 seems like a second stanza of a combined psalm, much like verses 7 and following are a second stanza of Psalm 19 (LXX 18). There is a new direction in theme and images, but there are connections also between the stanzas.

To summarize this 2nd point of divergence in numbering, we have 4 lines of evidence that demonstrate the original composition was combined. 1) The witness of the Septuagint itself (late first millennium B.C.), 2) The witness of the earliest Hebrew codices (circa A.D. 1000), 3) Absence of a superscription, and 4) evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls (circa 1st century B.C.).

We’ve got two more points of numbering divergence to go. I will save those for part 2 of this topic which I hope to finish in about a month. If you are kind enough to subscribe, you won’t miss the epic ending. :)