Psalm 22:16 "like a lion" or "pierced my hands and feet"

Let's look at the scroll fragment

The background

Psalm 22 has been controversial since early Christians understood it to be prophesy about the crucifixion of the Messiah. Not only does Jesus appear to quote this psalm from the cross (“My god, my god…why hast thou forsaken me?”) but the psalm contains several other images that are referenced in the crucifixion passages (e.g., casting lots for his clothes).

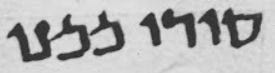

By far the most contentious line comes in verse 16b, “…they have pierced my hands and feet.” Or, if you follow the Hebrew Masoretic Text, “…like lions [they maul] my hands and feet.” The difference comes down to 1 letter: a waw(ו) versus a yod (י). Even in modern Hebrew script, you can see how similar these two letters are.

If the letter is a waw(ו), then the Greek Septuagint translation “they pierced” can make sense.

If the letter is a yod (י), then the Hebrew translation “like lions” can make sense.

I use the phrase “can make sense”, because in each case there difficulties with the translation from the Hebrew. By contrast the Greek of the early Church scriptures is not foggy. To quote the most recent and authoritative translation from the Greek (NETS - New English Translation of the Septuagint): “They gouged my hands and feet.” (Psalm 21[22]:16b). By the way, the psalms would have been among the earliest works translated into Greek after the Torah, probably in the 3rd or 2nd century before Christ.

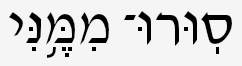

A fragment of an ancient scroll containing Psalm 22 was discovered in a cave in the wadi Nahal Hever in the West Bank during explorations in the 1960s. This fragment is not very easy to read, but it contains the line we care about in this post. And as it relates to the letter in question (the waw versus yod), the majority of epigraphers who have looked at the fragment agree it is a waw, supporting the traditional Christian reading of the verse as, “They pierced my hands and feet.” This post is not a survey of scholarly opinion. My claim is defensible, but I am not going to take the time to do that here. [For a starting point of scholarly coverage and bibliography for further reading, see The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls by James VanderKam and Peter Flint, p.125.]

Recently, a new line of doubt been advanced by some who admit that the controversial letter is a waw but want to defend the Hebrew Masoretic Text. The argument states that while a waw was written, we should read a yod. At first, this may seem like special pleading, but it is not unreasonable. It is a documented phenomenon that ancient Hebrew scribes for reasons of style or efficiency would sometimes make a final yod look like a waw. This phenomenon usually stems from the scribal act of “ligature”. Ligature is defined as, “where two or more graphemes or letters are joined to form a single glyph”. A familiar example is our ampersand sign (which combines the Latin letters ‘e’ and ‘t’ which are the Latin word ‘et’ (&). Another example we see in English is the merge of ‘a’ and ‘e’ to form æ.

Hebrew scribes sometimes did the same thing. This was particularly done at the end of words where a final yod was combined (or almost combined) with a previous letter, usually a letter whose foot would end where the waw-ish yod begins. The most common 2-letter combination of this is the nun+waw/yod (נו). Recall that Hebrew is written from right to left. The easiest way to think about this in English is to imagine writing the upper-case letter “L” followed by the letter “I”. Such a combined character would look something like a block “U”. Why would one do this? One can imagine that doing this might be faster (eliminating the need to lift the stylus and re-position it). It also saves linear space by smashing the two letters close together. If you have ever written with a quill and ink, you will also know that keeping the stylus on the parchment in a constant fluid manner, reduces the occurrence of drips and blotches.

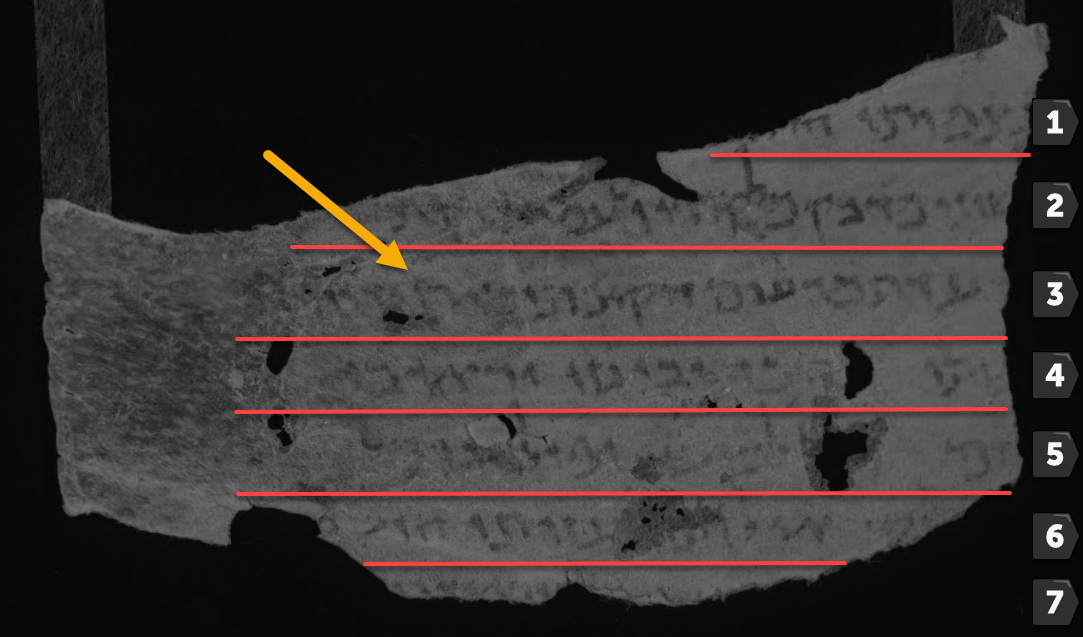

Here is a clear example of this practice from the great psalm scroll found at Qumran (11QPs(a)).

These are the first two words of Psalm 119:115 (סורו ממני - Depart from me…). You can see the last letter (i.e., the left-most letter in Hebrew) is actually attached to the letter that comes before it, a nun (English “N”). We know from context and later Masoretic texts that the last letter is supposed to be the letter yod (י), but it was clearly written as a ligatured waw(ו). The other word in this phrase contains two waws that are supposed to be waws. So, you can see for yourself that our scribe has given us a waw(ו) where he should have given us a yod (י).

Not all instances of a yod looking like a waw involve ligature. Particularly in the Qumran Psalm scroll, the scribe seemed to have been all over the place in this regard. In the words of the publisher of this scroll, James Sanders, “Waw and yod are distinguished in the scribe’s mind, not always by his pen...” (The Psalms Scroll of Qumran Cave 11, p. 7).

Some internet pundits who agree that the Nahal Hever fragment seems to contain a waw in our controversial word, point to the Psalms Scroll of cave 11 as evidence for why we should read the letter as a yod and not the waw.

I have not seen anyone analyze the Nahal Hever fragment itself for the presence of ligatured or otherwise lengthened yod. Hopefully, I have not lost you up to this point. The above was required background for what I present here as new.

Below is the official infrared image of the Nahal Hever fragment. The URL to the source is included in the caption. There are 7 lines of existing text with the bottom line being very fragmentary and difficult to decipher. While not nearly as clear as the Qumran Cave 11 psalms scroll, most of the lines are legible and the letters are clear enough for someone familiar with early first millenium Hebrew script. The orange arrow points to the controversial letter, which for the purposes of this blog post we will assume is a waw (whether or not it is to be read as a yod).

The bottom line

Before we go line by line and examine all of the occurrences of yod and waw, let me give the highlights for those of you who are busy and want to go do something else.

Of the 27 readable instances of waw and yod, none are a yod masquerading as a waw. They all play the letter expected by the Hebrew MT.

Only 2 of the 25 readable instances are questionable as to its intended letter, but only because of the scribal care (apparently). Four yod are not readable due to the condition of the fragment. The rest are clearly waw or yod.

There are 4 prime opportunities to expect a lengthened yod, two following a taw and two following a nun, including on the word immediately preceding the controversial word (הקיפוני), and the scribe took the bait none of these times.

Conclusion: While ligated and otherwise lengthened yods exist as a phenomenon in ancient Hebrew texts, they do not occur in the Nahal Hever fragment.

The detail

Next I will examine line by line all of the places where a yod or a waw is expected according to the Masoretic Text. I will judge each occurrence relative to its clarity as a yod or a waw.

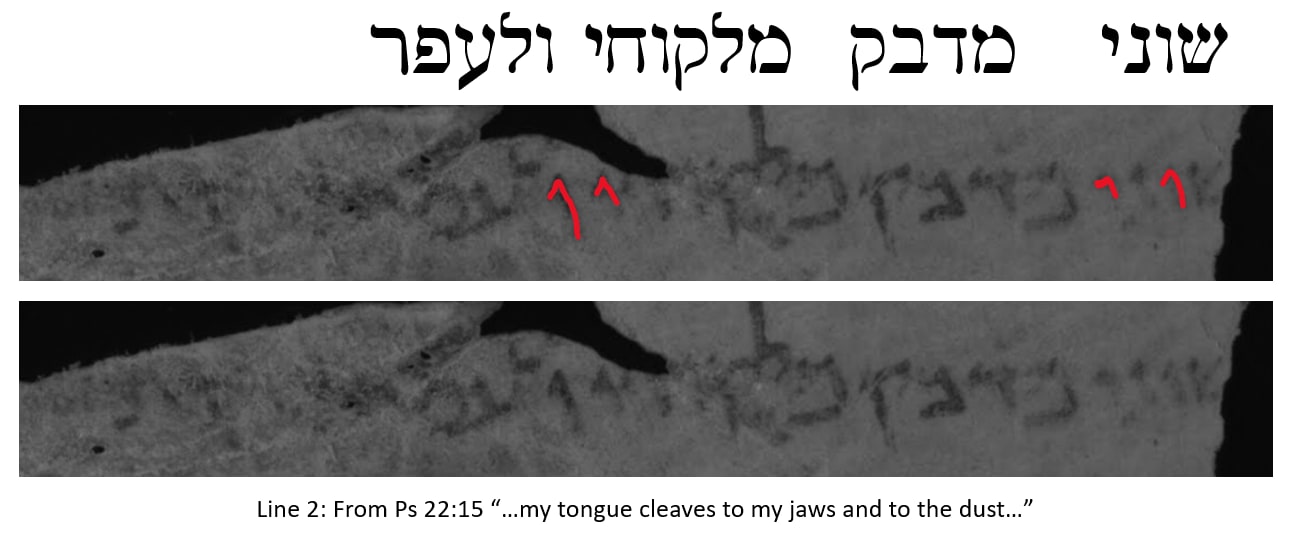

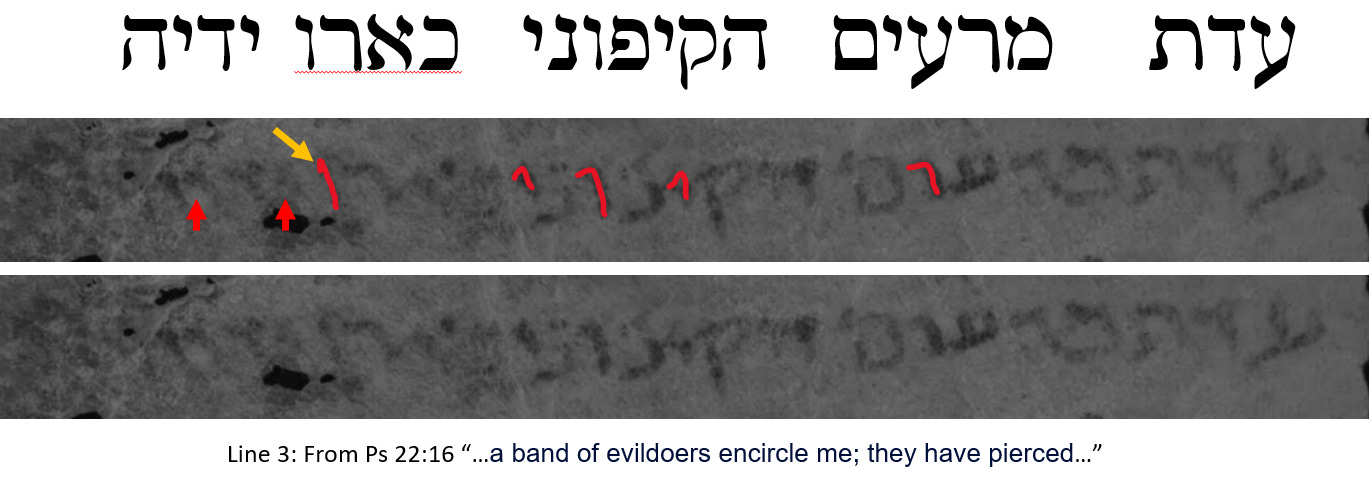

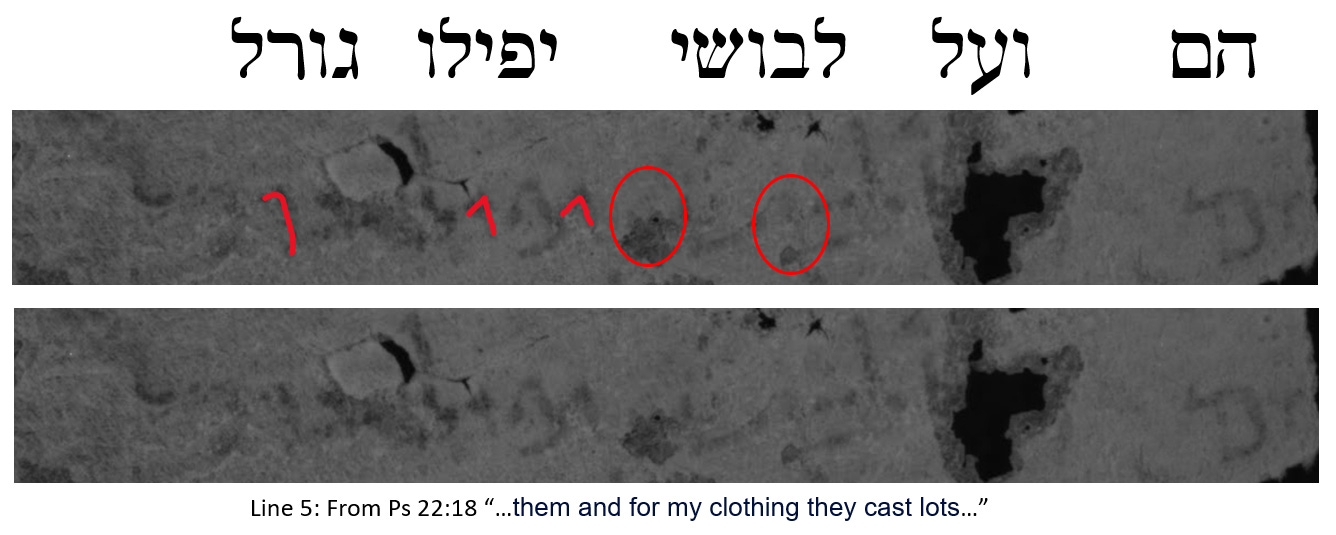

For each line I have attempted to roughly align the modern Hebrew font above the Nahal Hever text. The positioning is approximate and intended only as a reader help. Also, I have included two image snips of the line under review. One with my drawing over the letters and one without, so that you can form your own opinion.

While I do not claim to be a renowned epigrapher, I did study ancient texts and languages in my graduate work under Dr. William Dever at the University of Arizona. I have spent dozens to hundreds of hours reading texts from the Dead Sea region.

Each Hebrew letter has its typical form in each period of its history. In the case of the Dead Sea scroll material in general and the Nahal Hever fragment in particular, the typical yod when compared to the typical waw has:

A broader, more triangular head

A less vertical stance

A shorter leg

With these differentiators in mind, let us examine the text.

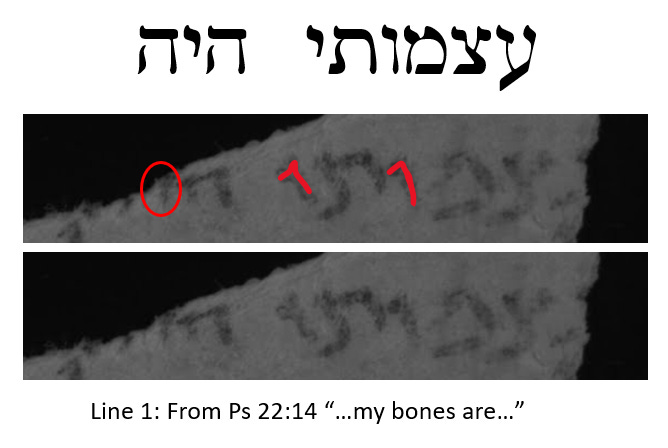

Line 1:

While the legs of the waw and yod in this line are of similar length, the stance and triangularity of the heads clarifies which is which. In addition, there is a clear gap between the leg of the yod and the foot of the taw to its right. The yod that I have circled is too partial for me to make a confident determination.

Note: The yod following the taw was a prime opportunity for ligature that was not taken.

Line 2:

There are two readable waw and yod apiece in this line. The giveaway on the first yod is the fact that the foot of the preceding nun (while faint) fully underlines the yod. The second yod is clearly distinguished from its adjacent waw in all three differentiators.

Line 3:

Line 3 contains the singular yod in the fragment that might look more like a waw, but it would be a bad example of a waw at that. From the darkness of the preceding letter ‘ayin, it appears that the scribe had just reloaded his stylus and it resulted in a rather messy yod. The other examples are clear, including the highlighted controversial waw. Notice the two vertical red arrows. These are pointing to two yods that the leading expert on the Nahal Hever fragment, Dr. Peter Flint, has published. Dr. Flint was able to handle the fragment himself as well as have access to enhance imaging like this snippet I found on the internet:

The closest I can find on publicly available sites is the following scanned infrared negative:

Given these images, and Dr. Flint’s publication of his opinion, I am going to include both of these yod in the respective column.

Line 4:

The first yod of line 4 has a longer leg than the ideal yod. However, the clear overlap with and gap between the foot of the preceding letter taw places it in the yod column. The two circled letters at the end of the line I have discarded from the statistics, because I am able to make an argument either way for these two. They are simply not legible enough in my opinion to make a judgement. Without the guidance of the known context of Psalm 22:17, I would say they are both yods. Considering this, they would cancel each other out statistically.

Line 5:

In line 5, I did not even bother to circle the first waw, because the parchment is damaged. The next waw and yod have been circled. I have discarded these two from the statistics; they are not legible in my opinion. The two legible yods have slightly long legs, but their heads and stance put them in the yod column. And when compared to the height of the pe that sits between them, the length of the legs makes it clear they are not waws.

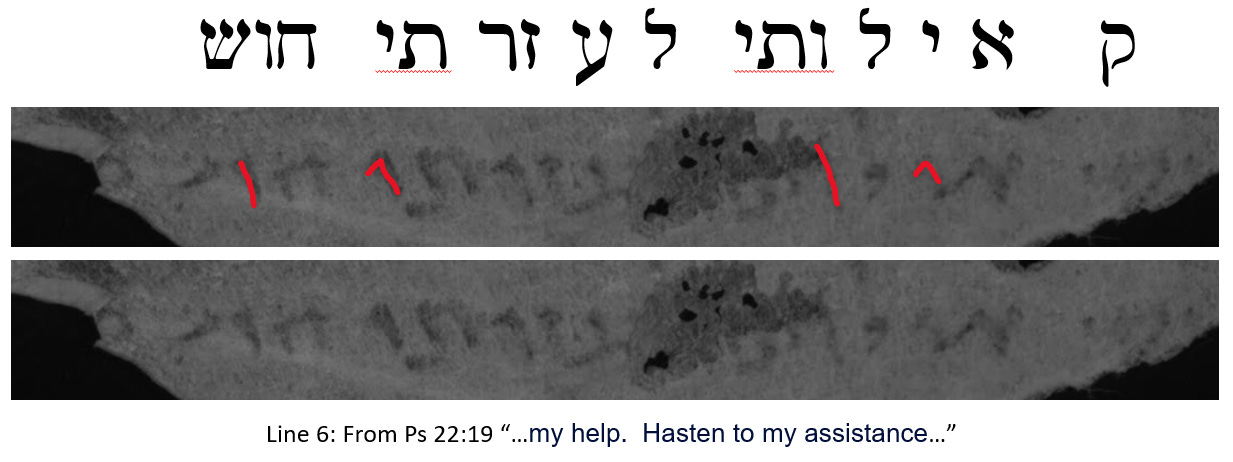

Line 6:

Stance, head and leg length are all clear in line 6. Two yod; two waw. One yod not considered as the parchment is damaged in that spot.

Line 7:

At first view, one might wonder how I can determine from this fragmentary line which word from Psalm 22 is written here. The answer is simple. The Nahal Hever fragment contains one line of text for each line of the poem. The lines are not run together to cram as many letters as possible onto the animal skin real estate. Instead, the poetic structure is retained. Based on this and the number of characters in verse 20 relative to the preceding verses, we know positionally which word should appear here.

I will admit to the possibility that the two letters in this last line cannot be confidently placed in the yod column. Exclude them if you wish, my conclusion remains the same:

There are no clear examples of yod presenting as waw in the Nahal Hever Psalm 22 fragment.