A verse your Bible should have but probably doesn't.

Restored Hebrew for missing verse Psalm 136:16b

In a previous post, I showed how the structure of Psalm 136 supplies strong evidence that the Hebrew Bible is missing a verse. Similar to how Psalm 145 is widely understood to be missing the so-called nun verse. In the case of Psalm 145, the Septuagint Greek contains the missing verse. But in the case of Psalm 136, the two oldest Greek manuscripts containing Psalm 136 (Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus) do not include the verse in question. However, proof that the verse actually did exist in Greek comes from two very different sources.

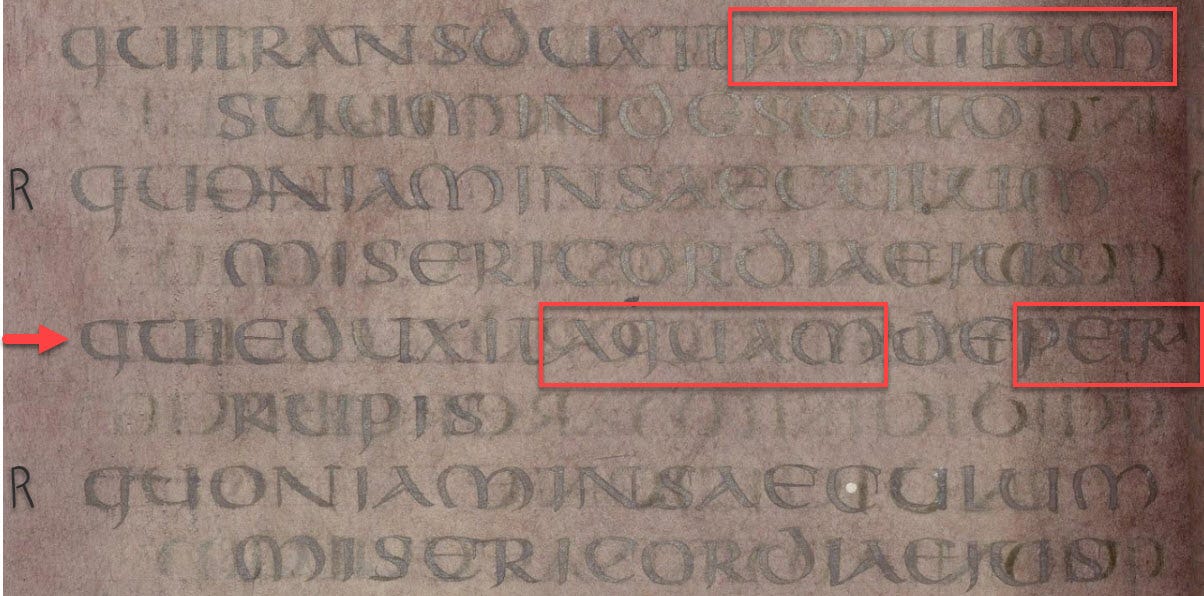

The first source is St. Jerome’s first edition of the Psalter. Chapter 12 of The Oxford Handbook of The Psalms is titled “Jerome’s Psalters”. In this helpful chapter, Scott Goins covers the history of Jerome’s three Psalter editions. As Goins explains, Jerome’s first Psalter was mostly a revision of the already existing Old Latin Psalter (a.k.a. Vetus Latina Psalter). While it is not entirely certain that this first Jerome Psalter even exists today, there is presented what is claimed to be a text of this Psalter in the absolutely gorgeous manuscript Psalter of St Germain. Firstly, this text is ancient, dating between AD 500 and 576. Second, it is gorgeous. Every page is purple tinted parchment (animal skin) written with silver and gold ink. Jerome notes in his intro to the book of Job that purple parchment was reserved for the most special books. Third, it follows the Septuagint numbering of the psalms. In the snip below from the start of the psalm on folio 267 you can make out the gold lettering roman numerals CXXXV (135). There is so much more to say about St Germain and this manuscript, but it is way off topic. The only thing that makes the text a bit of a challenge to read is the fact that the letters from the reverse side of the page are visible, albeit in reverse image.

The verse we care about today (verse 16) is on folio 268. Before we look at it I want to thank my classicist friend, Ty Wangsgaard, without whose Latin translation help I may not have learned about this manuscript.

In this image I have provided a couple of helpers. I’ve indicated the refrain with a capital “R” stamp on the left margin. “For his mercy endures forever.” The first red box surrounds the Latin word “populum” from which we get words like “population” and “populous”. It is the word “people” from verse 16, “who led His people through the wilderness…”. The red arrow points to the beginning of the verse that is missing from the Hebrew and the three major Greek uncial manuscripts: “Qui eduxit aquam de petra rupis…(refrain).” I have red-boxed the words “aquam” and “petra” as those should be familiar to most readers. Note the “A” at the end of “petra” was made small to fit on the page! This line reads: “He brought water out of the hard rock”. In a work from 1659 on the history of lapidary, the author Thomas Nicols indicates that the Latin phrase “petra rupis” referred to flint. Page 238. Unfortunately, the phrase “petra rupis” does not appear in any version of the Vulgate that I have searched, so I am not going to propose the Hebrew original based on the Latin. There is a similar phrase, “petra durissima” that is used in Deuteronomy 8:15, but I would like to base my text on an exact match.

In Jerome’s second version of the Psalter, which came to be known as the Gallican Psalter, he used a Greek source of the Psalms which did not contain this verse, so he dropped it. In his third edition, Jerome used available Hebrew manuscripts (during his stays in Syria and Palestine) and like the Masoretic Texts we have today, those Hebrew sources obviously did not include verse 16b either.

In a lengthy letter between Jerome and two priests who questioned over 80 of Jerome’s changes between his first edition and 2nd edition, the verse under investigation here does not come up. But a less significant difference in verse 7 is covered in the letter. This leads me to believe that perhaps Jerome never included the verse in question, even in his first edition, which was a revision of the existing Vetus Latina (Jerome, Epistle 106 (On the Psalms), Michael Graves, SBL Press 2022).

Suffice it to say that the oldest Latin text we have of the Psalms does include the line that I have argued is missing from the Hebrew based upon the structure of the psalm itself. As a reminder, the structure of the composition (if one accepts the structure I propose), is as old as the psalm’s composition (i.e., from the hand of the original author!).

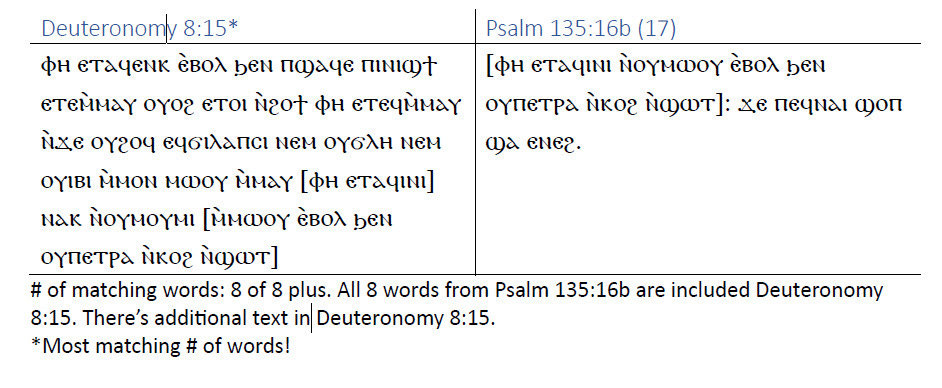

That is all I have time to say about the first line of evidence that the “water from the hard rock” verse was original. The second source of evidence comes from the Coptic (Egyptian language) scriptures. Here we have a textual tradition of our missing line that carries on to the present day. The current Coptic Psalter includes our missing line! There is little need for me to get my hands on the oldest Coptic manuscripts, although I would love to. The Coptic Psalter dates back to perhaps the 2nd century when the Psalms were already being heavily used in the the churches and a translation was needed in the Egyptian language of the common people.

I had enough Latin in high school to be dangerous, but my year of Egyptian in college was forgotten as soon as I graduated (Sorry, Dr. Hoffmeier!). So I had to rely on another friend, an Egyptian American, Joseph Fahim. I asked Joseph to compare the Coptic of the text of Psalm 136:16b with 5 Old Testament passages that relate to the Israelites getting water from the hard rock (Psalm 77:16, Psalm 113:8, Deuteronomy 8:15, Deuteronomy 32:13, and Numbers 20:8). Joseph did a lexical analysis of each passage and, by far, the closest text was Deuteronomy 8:15. In his words:

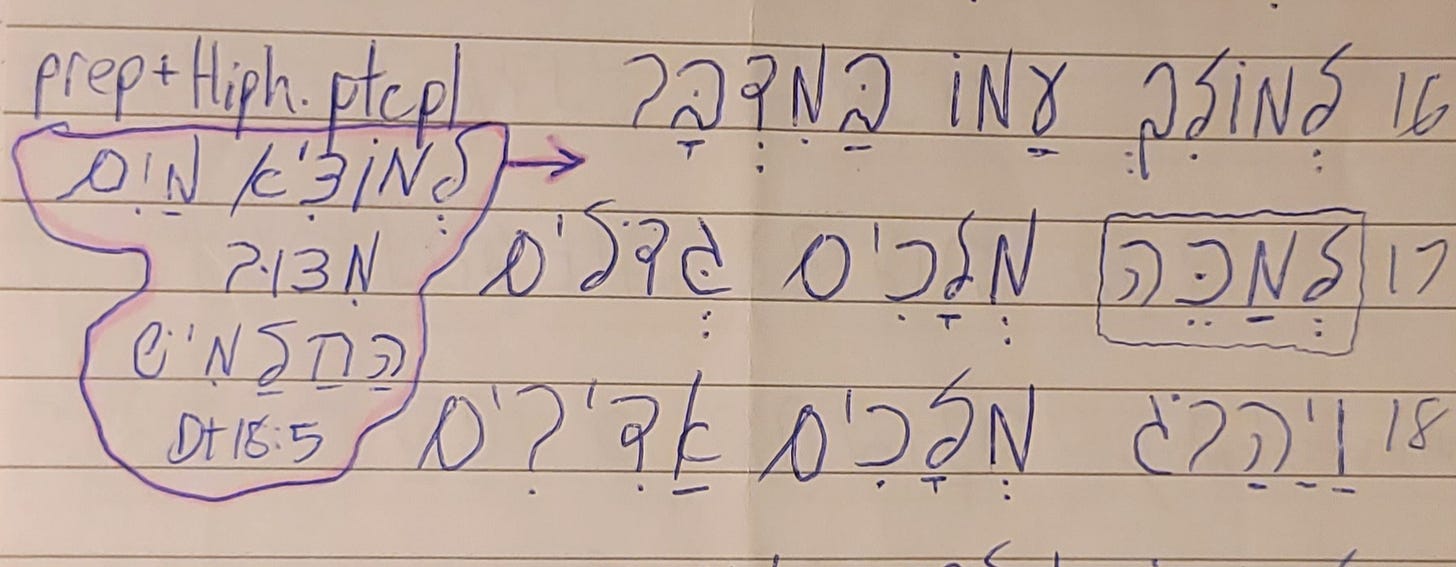

Huge thanks to Joseph for confirming what I was leaning toward from the Latin, and what Rahlf’s critical Greek edition pointed to as reference. Now we are able to triangulate between the Hebrew structure, the Old Latin, and the Coptic to produce what the original Hebrew may have looked like for this verse:

למוציא מים מצור החלמיש

כי לעולם חסדו

Transliteration:

LE-mo-tsee MA-yim mee-TSUR ha-kha-la-MEESH

kee le-oLAM khas-doe

Translation:

Who caused water to come out of the hard rock

His mercy endures forever.

In conclusion, it seems very clear to me that the original Greek and Hebrew had this additional verse. How did it get dropped? My guess is the cause was what manuscript experts call “haplography” or “eyeskip”. The scribe just made a visual mistake. If you have ever hand-copied long portions of written text, you may know how easy this is to do.

You may have been wondering about the image I included at the top of this blog post. I took this pic of my hand-written copy of Psalm 136 in Hebrew (modern, cursive script). I later included my re-constructed line on the left and circled/highlighted it. Notice my verse cross-reference below the verse: “Dt 18:5”. This, too, is a scribal error. The actual cross-reference is Dt 8:15. Scribal mistakes happen. Thankfully in the case of Psalm 136, we did not lose any deep theology or critical history. It was merely a recounting of an episode in the Israelites’ wilderness wanderings. Nevertheless, in the context of this poem/psalm, we are now able to fill what has been a 2000 year gap in the Hebrew text.